El Salvador's dirty warriors to face justice for 1989 massacre of six Jesuits priests, their housekeeper and her daughter

Senior commander Colonel Montano Morales could appear in court next year on charges of terrorism, murder and crimes against humanity

Colonel Orlando Inocente Montano Morales was working in a sweet factory on the outskirts of Boston when his inglorious war record finally caught up with him.

Col Montano Morales, a senior commander during El Salvador’s brutal civil war, had been quietly living in the United States for a decade when in May 2011 he and 19 former colleagues were indicted by a Spanish court on suspicion of participation in the 1989 massacre of six Jesuits priests, their housekeeper and her daughter.

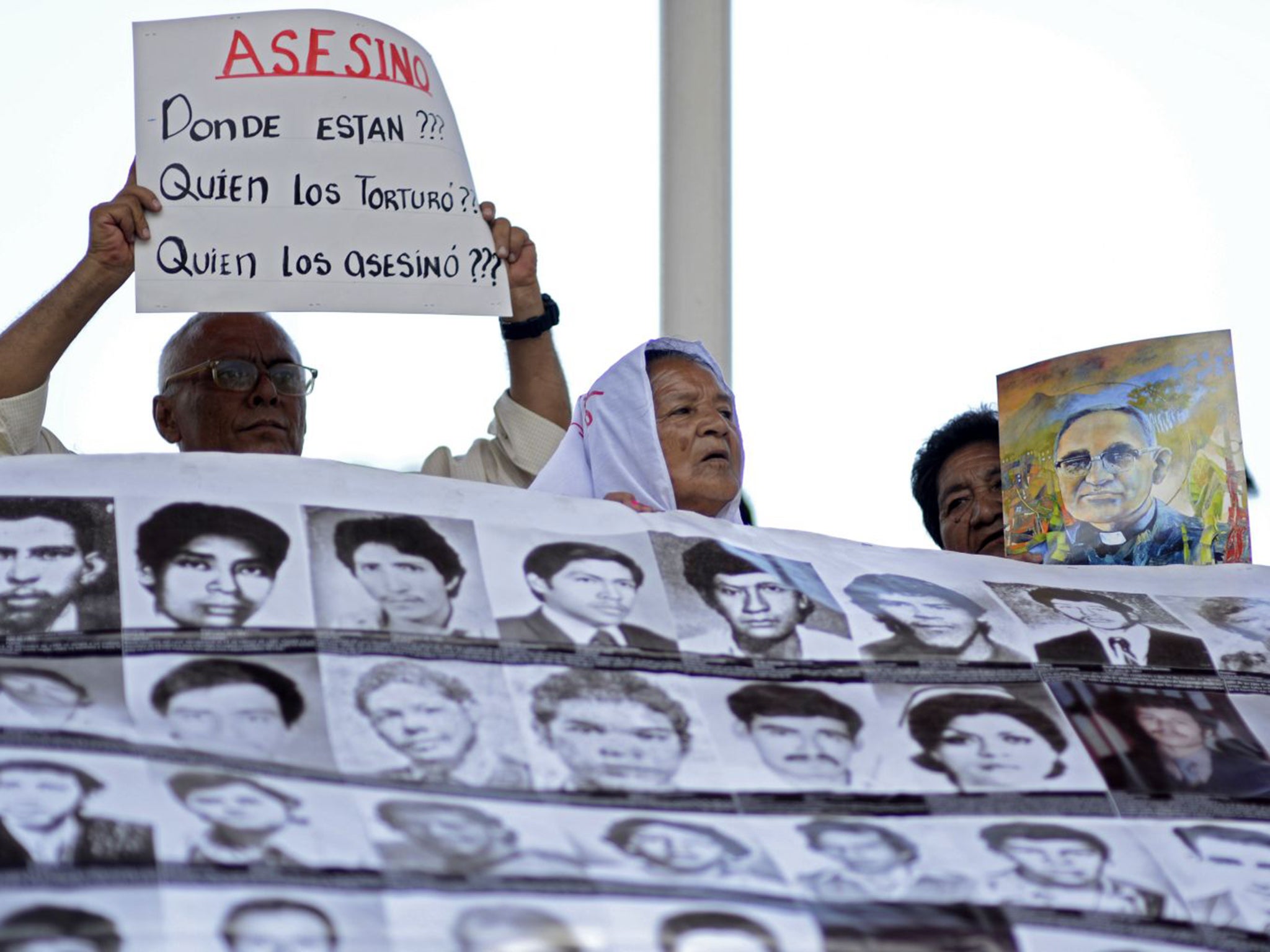

The massacre was one of the most notorious crimes of the war, which between 1980 and 1992 left 80,000 people dead, 8,000 missing and one million displaced – in a country the size of Wales. The vast majority of the atrocities were committed by US-backed armed forces and paramilitaries, according to the subsequent United Nations Truth Commission.

The Reagan government poured billions of dollars into El Salvador, and other Central American countries, to support right-wing military dictatorships fighting “dirty wars” against populist uprisings.

Earlier this month two landmark legal cases heralded a striking shift in US policy towards former Cold War allies. In the first, US prosecutors began extradition proceedings against Col Montano Morales which could see him in the dock next year facing charges of terrorism, murder and crimes against humanity.

The priests, five of them Spanish, were outspoken critics of the military dictatorship and heavily involved in truce negotiations when they, and the two witnesses, were gunned down in a military operation. Col Montano Morales, who held one of the top three military positions as vice-minister of public safety, is accused of playing a key role in planning the executions and the cover-up.

The full truth about the Jesuit murders has never been exposed despite investigations by the Truth Commission, US Congress and Scotland Yard, among others. Col Montano Morales will be the first high-ranking Salvadoran to face criminal scrutiny for a wartime atrocity.

“This will be one of the most important international criminal trials since Nuremburg,” said Carolyn Patty Blum, senior legal adviser at the San Francisco-based Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA) which brought the Jesuits case to Spain in 2008. “There will be strong reverberations for impunity and criminal accountability in El Salvador, but also internationally.”

By coincidence, on the day extradition proceedings began against Col Montano Morales, 8 April, one of his former military colleagues was deported after more than 25 years living in an upmarket Florida suburb. General Carlos Vides Casanova, a former defence minister, was expelled after the highest US immigration court ruled that he was ultimately responsible for multiple horrors committed by troops under his command. He also helped cover up serious crimes including the rape and execution of four US nuns in 1980 – another of the war’s most emblematic massacres, the court ruled.

Protests in Mexico over 43 missing students

Show all 13Vides Casanova, 77, is the highest ranking official from any country to be deported from the US under the 2004 “no safe haven” immigration law. He returned to El Salvador in handcuffs, where he was greeted by dignified survivors of his torture policies who have long campaigned for justice. He does not currently face any charges in El Salvador.

El Salvador’s war criminals have until now enjoyed impunity at home as a result of a controversial amnesty, passed by the military-allied Nationalist Republican Alliance government just five days after publication of the 1993 Truth Commission report.

The amnesty forced victims and human rights lawyers to get creative in their quest for justice outside El Salvador. The CJA, representing torture survivors and relatives of the slain, created a “most wanted list” of human rights criminals named by the Truth Commission reportedly living in the US. They, and more recently prosecutors under the Obama administration, have pursued them using a variety of civil, immigration and international laws.

The first big victory was in 2002 when Vides Casanova and another former defence minister, José Guillermo García, were found liable for torturing Salvadoran civilians by a Florida jury and ordered to pay $55m in compensation. Mr Garcia’s deportation trial is looming.

Col Montano Morales travelled to the US in 2001 when the FMLN (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front) rebels won a legislative majority, and it looked as if the massacre of the Jesuits might be re-investigated – the type of political change that triggered the collapse of amnesties in Chile, Argentina, Guatemala and Honduras.

Col Montano Morales was enjoying anonymity when the CJA tracked him down and he was indicted by Spanish authorities. A few months later he was arrested for immigration fraud, after it transpired that he had lied to obtain a humanitarian work permit. Col Montano Morales, 73, was jailed for 22 months for immigration offences after the judge heard evidence from leading El Salvador expert Terry Karl, professor of political sciences at Stanford University, California.

Professor Karl documented at least 1,169 human rights abuses – including 65 extra-judicial killings of named individuals, 51 disappearances and 520 torture victims – carried out by units under Col Montano Morales’ command before the Jesuits massacre. Col Montano Morales, who has just completed his immigration sentence, will remain incarcerated until his anticipated extradition.

Professor Karl told The Independent: “These [Casanova and Morales] are landmark cases, not only because they are actions against former US allies that conducted ‘dirty wars’ with the support of the Reagan administration, but also because they set important new legal precedents for the deportation and extradition of war criminals in the defence of human rights.”

Last week’s historic events pile further pressure on Salvadoran authorities to annul the amnesty – long ruled illegal by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights – and deal with past horrors.

The FMLN government no longer has a parliamentary majority but the El Salvador Supreme Court is expected to rule imminently on an unconstitutionality case which could lead to the amnesty being wholly or partially, rescinded. The traditionally military-aligned court may then be forced to reconsider extraditing the other 17 wanted by Spain (one died, the other has not been located) – which it refused in 2011 in contravention of a bilateral treaty.

El Salvador’s most revered martyr, Archbishop Oscar Romero, whose assassination triggered the war, will next month be beatified.

But, 23 years since the end of the war, the country’s six million people are now terrorised by jaw-dropping levels of violence linked to street gangs, organised crime, corruption and on-going impunity. Last month, one of the bloodiest on record, 481 people were murdered.

For many, the violence is rooted in the failure to address the crimes of the past. Professor Karl said: “Only the end of impunity can help to bring forward more historical truth, honour the memory of victims, and reduce the astonishing level of murder that still racks El Salvador.”

Two victims turned witnesses

Daniel Alvarado was an engineering student in 1983 when he was abducted while watching a football match at a friend’s house – during General Vides’ reign as Defence Minister. He was brutally tortured in police headquarters in order to obtain a false confession for the assassination of a US military advisor. His confession was rejected by the Americans after they ran a lie-detector test – uncovered by CJA lawyers in declassified US government documents.

Alvarado, who gave evidence at the Vides deportation trial, said: “The [American] trials are important because they showed the world that these men living in the US pretending to be normal are actually war criminals… The US not only has the responsibility to expel these criminals, but also to repair in some way the damage that they helped these individuals cause.”

Neris Amanda Gonzales, a lay church worker, was abducted while eight-months pregnant by uniformed National Guard soldiers, under the command of Vides and Garcia. For two weeks she was brutally raped, given electric shocks, and held down whilst soldiers jumped on her pregnant belly, before being dumped unconscious on a rubbish dump. Gonzales survived; her infant son died aged two-months. She was at the airport last week as Vides landed in El Salvador.

“Our amnesty law allowed Vides to hide from justice and enjoy the privileges and fun of Daytona Beach [in Florida], but he could not escape American justice which exposed his atrocities against humanity. We now eagerly await the Supreme Court ruling because we the victims have never given up hope of seeing these criminals in the dock facing justice in a Salvadoran courtroom.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies