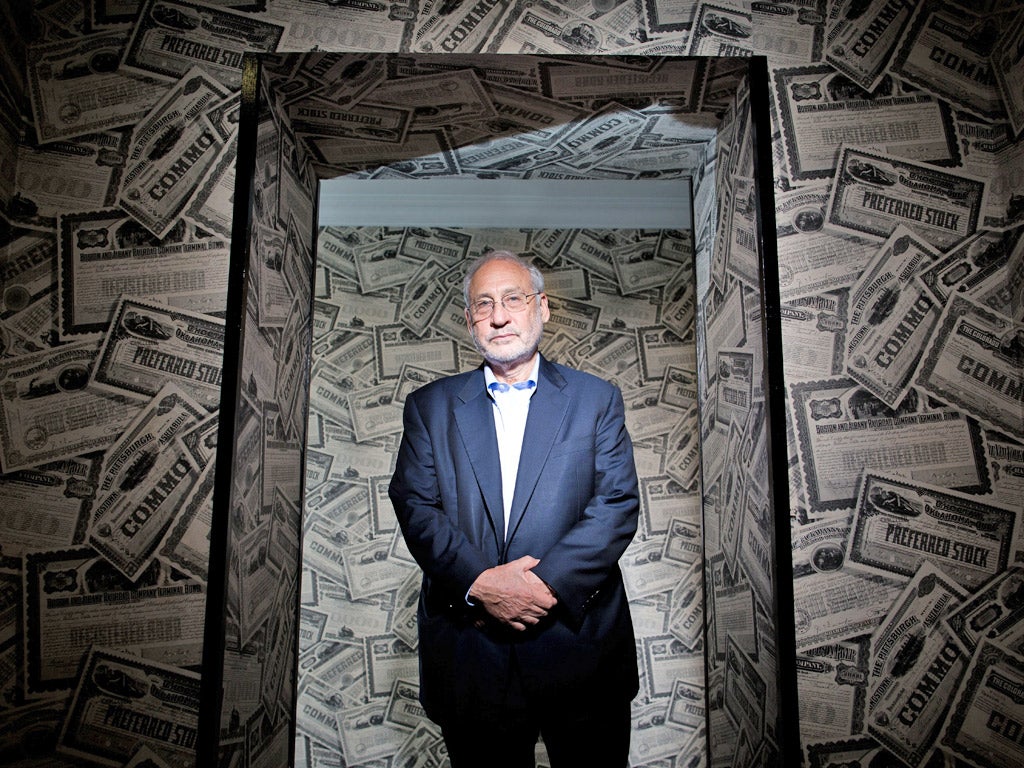

Joseph Stiglitz: Man who ran World Bank calls for bankers to face the music

Joseph Stiglitz tells Ben Chu that rogue financiers have proven that regulation must get tougher

The Barclays Libor scandal may have shocked the British public, but Joseph Stiglitz saw it coming decades ago. And he's convinced that jailing bankers is the best way to curb market abuses. A towering genius of economics, Stiglitz wrote a series of papers in the 1970s and 1980s explaining how when some individuals have access to privileged knowledge that others don't, free markets yield bad outcomes for wider society. That insight (known as the theory of "asymmetric information") won Stiglitz the Nobel Prize for economics in 2001.

And he has leveraged those credentials relentlessly ever since to batter at the walls of "free market fundamentalism".

It is a crusade that has taken Stiglitz from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to the Clinton White House, to the World Bank, to the Occupy Wall Street camp and now, to London, to promote his new book The Price of Inequality.

And kind fortune has engineered it so that Stiglitz's UK trip has coincided with a perfect example of the repellent consequences of asymmetric information.

When traders working for Barclays rigged the Libor interest rate and flogged toxic financial derivatives – using their privileged position in the financial system to make profits at the expense of their customers – they were unwittingly proving Stiglitz right.

"It's a textbook illustration," Stiglitz said. "Where there are these asymmetries a lot of these activities are directed at rent seeking [appropriating resources from someone else rather than creating new wealth]. That was one of my original points. It wasn't about productivity, it was taking advantage."

Yet Stiglitz's interest in the abuses of banks extends beyond the academic. He argues that breaking the economic and political power that has been amassed by the financial sector in recent decades, especially in the US and the UK, is essential if we are to build a more just and prosperous society. The first step, he says, is sending some bankers to jail. " That ought to change. That means legislation. Banks and others have engaged in rent seeking, creating inequality, ripping off other people, and none of them have gone to jail."

Next, politicians need to stop spending so much time listening to the financial lobby, which, according to Stiglitz, demonstrates its spectacular economic ignorance whenever it claims that curbs on banks' activities will damage the broader economy.

This talk of economic ignorance brings us to the eurozone crisis and the extreme austerity policies being pursued. Stiglitz is depressed. In 2000 he resigned from the World Bank and launched an excoriating attack on the way it and its sister institution, the International Monetary Fund, handled the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s. He condemned the IMF for imposing brutal and inappropriate adjustment policies on bailed out nations – medicine which, he argued, merely pushed nations further into crisis. "For me there's some nostalgia here," he says.

Does he see any hope for the eurozone, I ask, or is it now heading, inevitably, for a breakup? "It is a train that can still be stopped" he says. "But the relevant question is the politics in Germany. Have they created in their rhetoric a dynamic that makes it difficult to stop? In particular [German Chancellor] Angela Merkel's rhetoric that the crisis was caused by profligacy. She's framed the issue as profligacy, rather than framing it as 'the European system is fundamentally flawed' ".

The central argument of his latest oeuvre is that the huge inequalities of income and wealth that have developed in the US and elsewhere in the West over recent decades are not only unjust in themselves but are retarding growth.

"Every economy needs lots of public investments – roads, technology, education," he says. "In a democracy you're going to get more of those investments if you have more equity. Because as societies get divided, the rich worry that you will use the power of the state to redistribute. They therefore want to restrict the power of the state so you wind up with weaker states, weaker public investments and weaker growth."

It's an elegantly simple proposition. And one that logically points to a radical manifesto of redistribution and higher taxation in the name of the general public good. Time will tell whether this comes to be regarded as another manifestation of towering economic genius. But, for now, crusading Stiglitz has one more weapon in his hands with which to batter down those walls of folly.

Joseph Stiglitz: A life in brief

Born: Gary, Indiana in 1943

Educated: Amherst college, in New England. Later, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Career: Nobel Prize-winning economist and former member of President Clinton's administration during his time in the White House and, latterly, an adviser to President Obama. He is currently a professor at Columbia University

Family: Married to Anya Schiffrin, a professor at Columbia

FYI: Stiglitz' home town also produced Paul Samuelson, the first American winner of the Nobel Prize for economics

Stiglitz wrote of Samuelson: "Paul allegedly once wrote a letter of recommendation for me which summarised my accomplishments by saying that I was the best economist from Gary, Indiana."

"The Price of Inequality" by Joseph Stiglitz is published by Allen Lane

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies