Parkinson's patient has foetus brain cells injected into brain for first time in 20 years

Trials of the technique were abandoned two decades ago after patients showed little improvement after two years, and some suffered severe side effects

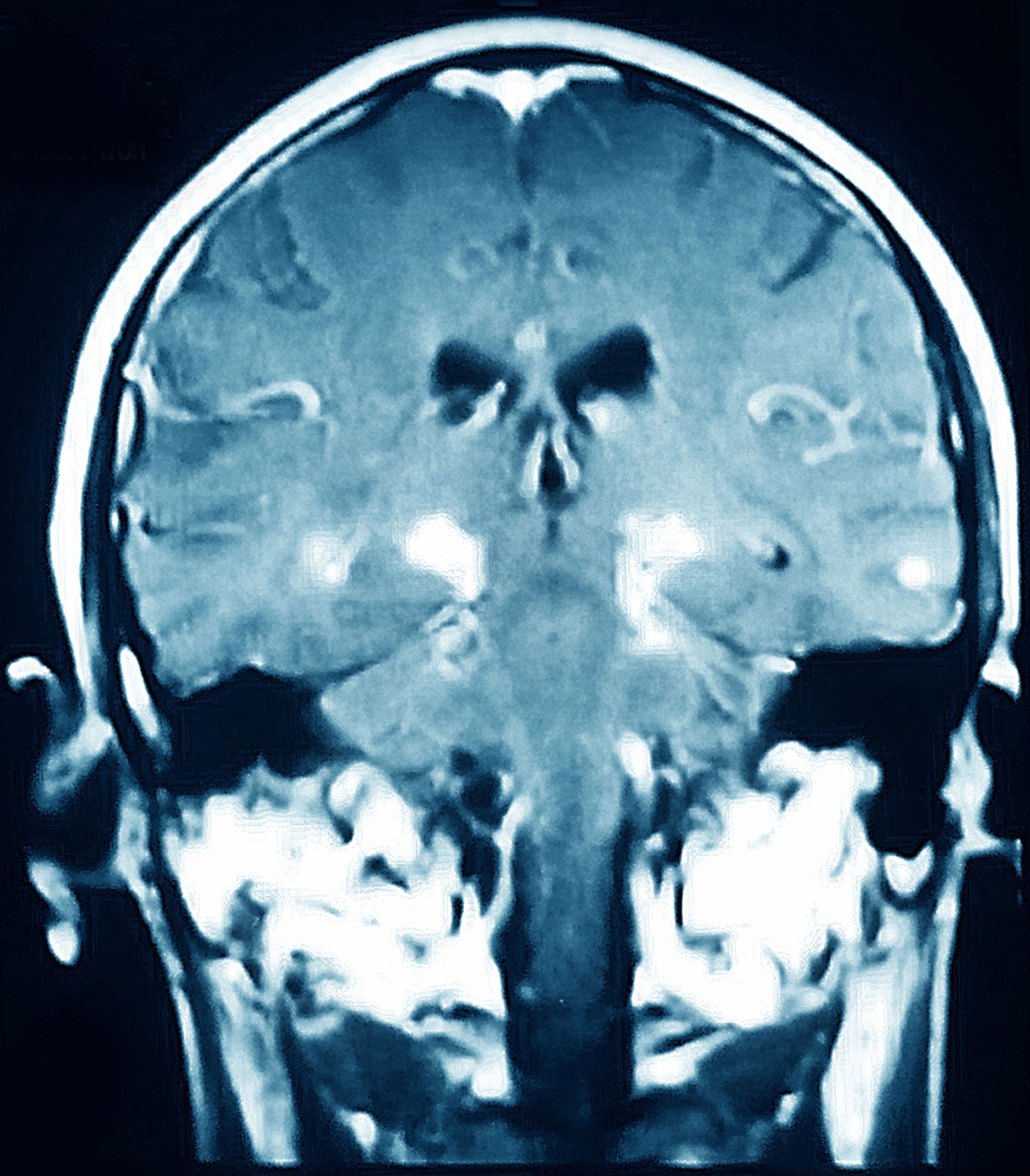

A Parkinson’s patient in Cambridge has had brain cells donated from a foetus injected into his brain – the first person in 20 years to undergo the procedure.

Trials of the technique were abandoned two decades ago after patients showed little improvement after two years, and some suffered severe side effects.

However, since then, some of the people who received the treatment in Sweden and the USA have gone on to experience remarkable improvements in their condition, with some even able to come off their Parkinson’s medication.

Researchers now realise that it takes several years for the foetal brain cells to “bed in”, according to a report in New Scientist, and are embarking upon a new trial that they hope will answer once and for all whether cell treatments could be the answer to remedy the debilitating condition.

The patient, a 50-year-old man, was treated at Addenbrookes Hospital in Cambridge on 18 May.

Foetal brain cells are thought to work by regenerating the brain’s ability to produce the chemical dopamine, which serves many functions in the brain, including control of movement. In Parkinson’s disease, dopamine-producing cells in a key part of the brain called the substantia nigra die off, leading to loss of muscle control.

The new international trial, spearheaded by experts at Cambridge University and involving 19 patients, will look again at whether foetal brain cell injections work in the long-term, drawing on lessons from previous trials in the 1980s and 1990s, which found that some patients suffered from overactive dopamine production and incontrollable movements – possibly because inappropriate tissue was used in transplants.

If successful the trial would not lead to foetal cell injections becoming a possible treatment for many patients. Donations must come from women who have terminated pregnancies, making it logistically impossible. Cells from at least three foetuses are required for each side of the brain, and there are 127,000 Parkinson’s sufferers in the UK alone.

Instead, proof that cell treatments for Parkinson’s can work, would become a “springboard” for pioneering work using stem cells, instead of foetal cells, said Claire Bale, research communications manager at the charity Parkinson’s UK.

“These foetal transplants have been done in the past, in the 80s and early 90s there were trials, most of them in Sweden,” she said. “Some of the patients who went into those trials did really well. I have spoken to some of them who were able to come off most of their Parkinson’s medication – this was 15 years after the transplant – a phenomenal response.”

“It is hoped that this [new] trial will give the definitive answer and show that transplantation works. If it does show that then it will be the springboard to the next phase, which is stem cell therapy.”

Professor Roger Barker of the Cambridge University John van Geest Centre for Brain Repair, who is leading the investigations, told New Scientist that the procedure, “seemed to go fine”.

“We would expect that if we do both sides [of the brain], he will see an improvement in around six months to a year,” he added, with maximum benefits predicted to happen within three to five years.

Trials of stem cell treatments could be underway by as early as 2017. Currently Parkinson’s patients are treated using drugs that raise dopamine levels, but can have side effects including involuntary movements. Surgery – known as deep brain stimulation – is also available, but only alleviates symptoms and is not a cure.

“Cell transplants offer something completely different: the idea we could possibly repair the brain and repair the damage that has been done by giving people with Parkinson’s new and healthy dopamine-producing nerve cells,” said Bale. “So their brains work properly again and they don’t need to be taking drugs with all these side effects.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies