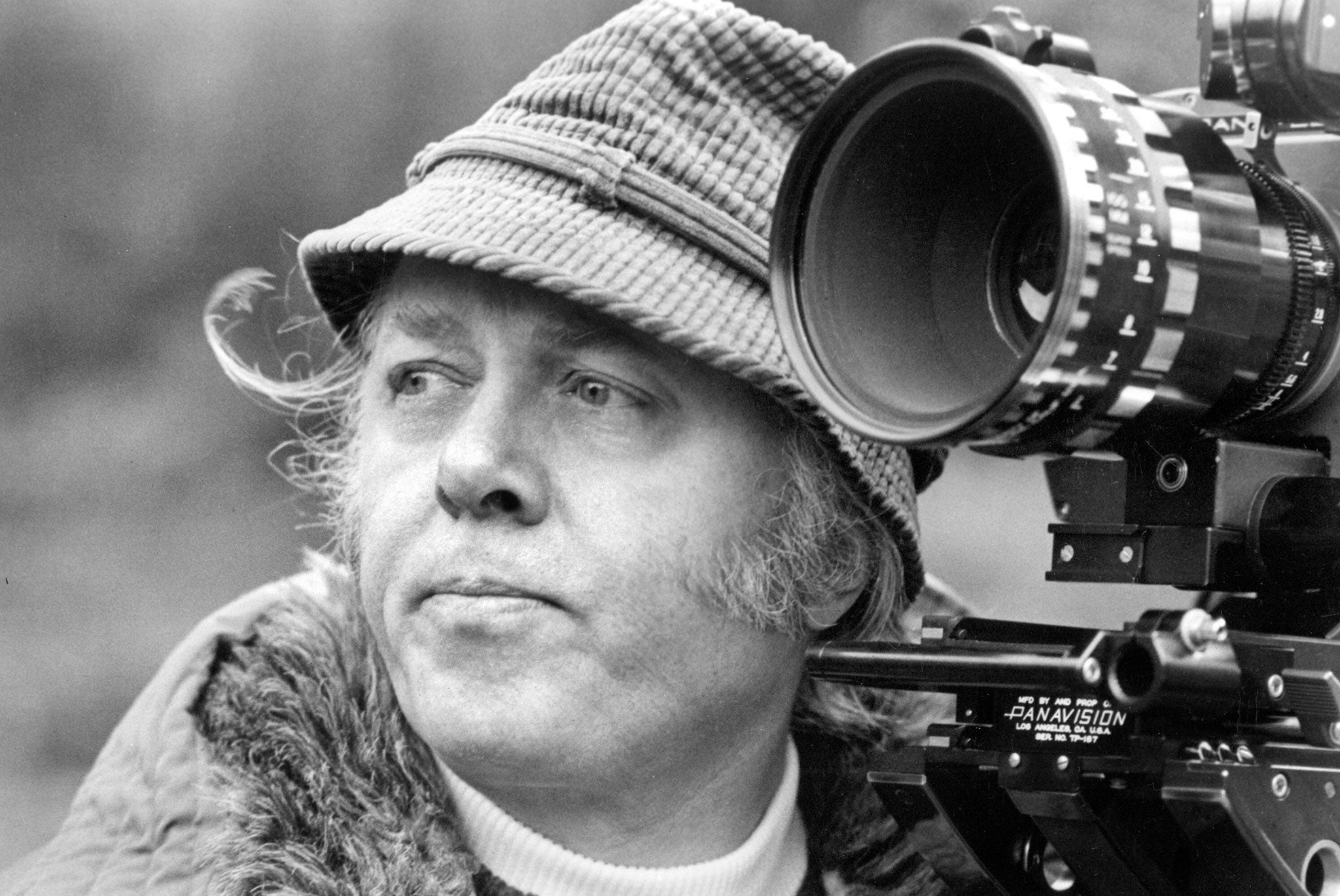

Richard Attenborough: A film too far

The late Richard Attenborough was a screen giant. So why did he fail in his attempt to make a film about the 18th-century radical Thomas Paine?

Look at your local film listings and you will realise that the type of cinema that Richard Attenborough championed has been almost entirely extinguished.

Attenborough may have appeared in Jurassic Park but he wasn’t a director who would have made Marvel adaptations or new instalments of Sin City and The Expendables. He had an idealistic (and now deeply unfashionable) view of film as a medium not just for entertainment but for dealing with social and political questions.

Attenborough’s 20-year battle to make his Oscar-winning biopic Gandhi (1982) is well chronicled. Far less well known to the public is his equally lengthy but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to make a film about 18th-century writer, political theorist and revolutionary Thomas Paine, author of Rights of Man (1791.)

The idea for the film first came to Attenborough in the late 1980s, when he was in his pomp. Attenborough commissioned a screenplay, These Are the Times, from playwright Trevor Griffiths and was delighted with what Griffiths delivered. This was going to be a movie on a huge scale – an epic to match Warren Beatty’s Reds (which Griffiths had also scripted.) With his customary optimism, Attenborough was convinced he would be able to make it, but, as the years passed and Griffiths continued to write new drafts, backers failed to materialise.

“The financiers aren’t interested in the subjects I want to make,” Attenborough stated. “Trevor Griffiths’ script for Tom Paine is one of the best I’ve read but it needs $65 or 75 million. It’s period, it’s religion, it’s politics, it’s morality. They ignore the fact that there are some wonderful, evocative man-to-man battles involved. There’s Washington, Robespierre, Danton and two great love affairs.”

It may have been that Attenborough saw a little of himself in Paine. Here was an Englishman who had been involved in the writing of the American Declaration of Independence and had visited France shortly after the Revolution. Paine was a radical who believed in free education and the emancipation of women. He also led an extraordinarily colourful private life, full of travel, tumult and controversy.

The Tom Paine project had some surprising champions. When the screenplay was published, US sci-fi writer Kurt Vonnegut was an immediate enthusiast. According to Trevor Griffiths’ website, Vonnegut “loved it so much he declared that he wished he had written it, and requested dozens of copies to send to friends in Hollywood, some of whom did indeed promise to try to get the film made”. He called the screenplay “a gorgeous pageant of American idealism”.

Tom Stoppard was equally enthusiastic, describing the screenplay as “magnificent, huge, human, an education in history, of course, but also in the human spirit.

It was Attenborough’s misfortune that films about American idealism and the human spirit were not then much in vogue. The project was on far too big a scale to be financed as a British or European art house movie but the US studios wouldn’t go near it. The box-office failure of more modestly budgeted Attenborough films like In Love and War (1996) and Grey Owl (1999) didn’t reassure financiers either. In interviews, he floated names of actors he would like to appear in the Paine film – maybe Daniel Day-Lewis to star and Anthony Hopkins to play Benjamin Franklin. He even suggested there could be a role for Meryl Streep.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

On all of his projects, he was utterly committed. Screenwriter William Goldman writes admiringly in Adventures in the Screen Trade of Attenborough’s ferocious work ethic when making war epic A Bridge Too Far. “It was twenty-four months, seven days a week, for an average of eighteen hours a day,” Goldman recalled of the director’s work schedule. He brought the film in on schedule and under budget – and then went to bed and slept around the clock for three days solid. That wasn’t even a passion project for him. One can only guess that he would have worked even harder on the Thomas Paine film.

With Hollywood studio funding hard to come by, there was even talk of crowd funding. Two Luton film-makers, Neil Fox and Justin Doherty, launched a website to gather together finance for the project.

“It was probably one of the world’s first attempted – and failed – crowd-funding things,” Doherty recalls. He and Fox were inspired to help Attenborough after seeing him talk at a regional press conference for Closing the Ring (2007). “He was so energetic. He must have been about 83. We met him afterwards. He talked in that press conference about the Thomas Paine film – how he was struggling to make it. You hear these stories all the time but it is remarkable that someone like him would struggle to make a film about such an interesting and important historical figure.”

Unsurprisingly, their attempts at raising £40m soon foundered.

The years were catching up with him but, a decade ago, when Attenborough turned 80, he still sincerely believed that he would one day make the Paine film. When Griffiths published the screenplay, he dedicated it to Attenborough, “comrade and conductor on this long march”.

In the end, Griffiths’ version of Paine’s story was dramatised – first in 2008 as a two part BBC radio play starring Jonathan Pryce as Paine and Alan Howard as Benjamin Franklin, and following that, under a new title A New World, as a three-hour play at the Globe Theatre the following year.

By then, it was apparent that Attenborough’s film version would never be green-lit. In a way, it was a compliment to him that it wasn’t. Attenborough, the friend of Princess Diana and well-connected lobbyist for innumerable good causes, may have seemed the quintessential establishment figure. The Thomas Paine biopic, though, was far too radical a project for its times.

It wasn’t just the expense that put off potential backers. What almost certainly alarmed them even more were the ideas. Given the choice between making action movies and telling the stories of the lives of political visionaries, there was only one direction in which the film industry was going to go.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies