The talent myth: How to maximise your creative potential

If you thought that geniuses were born not bred, you'd be wrong, says Daniel Coyle. He visited centres of excellence across the world and discovered that, if we all just followed a few key rules, success could be ours for the taking.

A few years back, on an assignment for a magazine, I began visiting talent hotbeds: tiny places that produce large numbers of world-class performers in sports, art, music, business, maths, and other disciplines.

My research also took me to a different sort of hotbed: the laboratories and research centres around the country investigating the new science of talent development. For centuries, people have instinctively assumed that talent is largely innate, a gift given out at birth. But now, thanks to the work of a wide-ranging team of scientists, including Dr K Anders Ericsson, Dr Douglas Fields, and Dr Robert Bjork, the old beliefs about talent are being overturned. In their place, a new view is being established, one in which talent is determined far less by our genes and far more by our actions: specifically, the combination of intensive practice and motivation that produces brain growth.

It started when I visited my first talent hotbed, the Spartak Tennis Club in Moscow. On my first morning there, I walked in to see a line of players swinging their racquets in slow motion, without the ball, as a teacher made small, precise adjustments to their form. I noticed the way the teachers routinely mixed age groups. I noticed the riveted, laser-like looks in the younger players' eyes as they watched the older stars, as if they were burning images of perfect forehands and backhands on to their brains. In my brain, a thought began to take shape.

From that point on, whenever I spotted a nugget of advice or a potentially useful method, I jotted it in my notebook and marked the page with an electric-pink Post-it. I scribbled down tips like "Always exaggerate new moves"; "Shrink the practice space"; and (my personal favourite) "Take lots of naps". Over the course of the year, a forest of pink grew along the edges of my notebook.

I kept travelling, visiting more talent hotbeds, talking to more master teachers, and adding more pink Post-its. At some point I realised that I needed to organise all this advice and put it in one place… What follows is a collection of simple, practical tips – all field-tested and scientifically sound – for improving skills, taken directly from the hotbeds I visited and the scientists who research them.

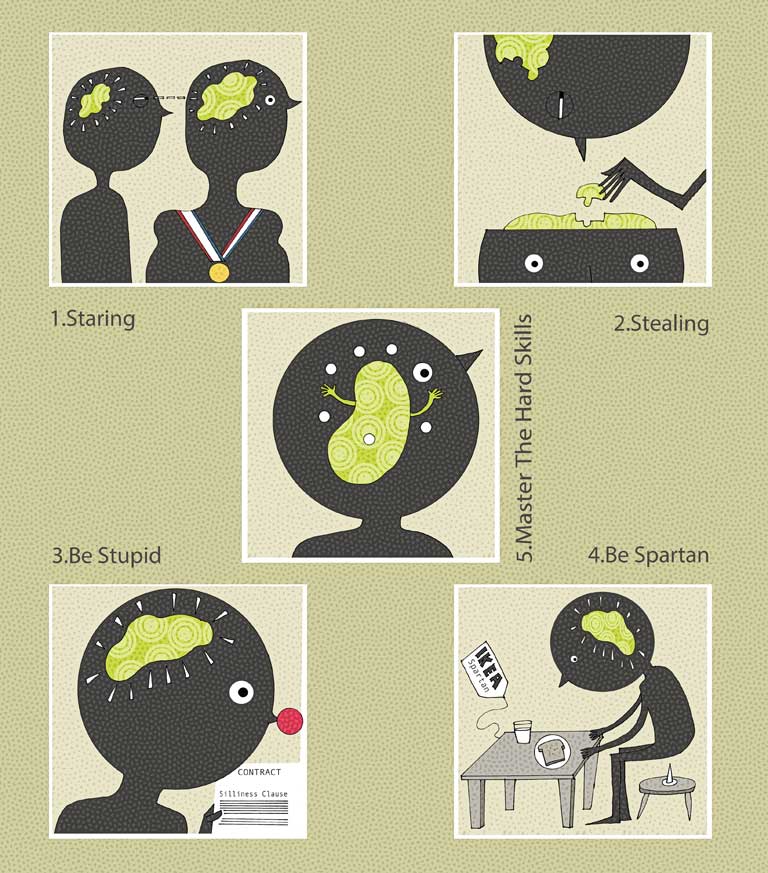

1. Stare at who you want to become

If you were to visit a dozen talent hotbeds tomorrow, you would be struck by how much time the learners spend observing top performers. When I say observing, I'm not talking about passively watching. I'm talking about staring – the kind of raw, unblinking, intensely-absorbed gazes you see in hungry cats or newborn babies.

We each live with a 'windshield' of people in front of us; one of the keys to igniting your motivation is to fill your windshield with vivid images of your future self, and to stare at them every day. Studies show that even a brief connection with a role model can vastly increase unconscious motivation. For example, being told that you share a birthday with a mathematician can improve the amount of effort you're willing to put into difficult maths tasks by 62 per cent. f

Many talent hotbeds are fuelled by the windshield phenomenon. In 1997, there were no South Korean golfers on the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) Tour. Today there are more than 40, winning one third of all events. What happened? One golfer succeeded (Se Ri Pak, who won two major tournaments in 1998) and, through her, hundreds of South Korean girls were ignited by a new vision of their future selves. As the South Korean golfer Christina Kim put it, "You say to yourself, 'If she can do it, why can't I?'."

Think of your windshield as an energy source for your brain. Use pictures or, better, video. One idea: bookmark a few YouTube videos, and watch them before you practise, or at night before you go to bed.

2. Steal without apology

We are often told that talented people acquire their skill by following their 'natural instincts'. This sounds nice, but in fact it is baloney. All improvement is about absorbing and applying new information, and the best source of information is top performers. So steal it.

Stealing has a long tradition in art, sports, and design, where it often goes by the name of 'influence'. The young Steve Jobs stole the idea for the computer mouse and drop-down menus from the Xerox Palo Alto Research Centre. The young Beatles stole the high "wooooo" sounds in "She Loves You" and "Twist and Shout" from their idol Little Richard. The young Babe Ruth based his swing on the mighty uppercut of his hero, Shoeless Joe Jackson. As Pablo Picasso put it, "Good artists borrow. Great artists steal".

Stealing helps explain why the younger members of musical families so often are also the most talented. (A partial list: the Bee Gees' younger brother, Andy Gibb; Michael Jackson; the youngest Jonas Brother, Nick. Not to mention Mozart and JS Bach, both babies of their families.) The difference can be explained partly by the windshield phenomenon (see Tip 1) and partly by theft. As they grow up, the younger kids have far more opportunity to watch their older siblings perform, to mimic, to see what works and what doesn't. In other words, to steal.

When you steal, focus on specifics, not general impressions. Capture concrete facts: the angle of a golfer's left elbow at the top of the backswing; the curve of a surgeon's wrist; the exact length of time a comedian pauses before delivering the punchline. Ask yourself: what, exactly, are the critical moves here? How do they perform those moves differently than I do?

3. Be willing to be stupid

Some places encourage 'productive mistakes' by establishing rules that encourage people to take risks. Google offers '20 per cent time', where workers are given a portion of their work time to spend on private, non-approved projects they are passionate about, and thus ones for which they are more likely to take risks.

Living-Social, the e-commerce company, has a rule of thumb for employees: once a week, make a decision at work that scares you. Whatever the strategy, the goal is always the same: to encourage reaching, and to reinterpret mistakes so that they're not verdicts, but the information you use to navigate to the correct move.

4. Choose spartan over luxurious

We love state-of-the-art practice facilities, oak-panelled corner offices, spotless locker rooms, and fluffy towels. Which is a shame, because luxury is a motivational narcotic: it signals our unconscious minds to give less effort. It whispers, relax, you've made it.

Talent hotbeds are not luxurious. Top music camps consist mainly of rundown cabins. The North Baltimore Aquatic Club, which produced Michael Phelps and four other Olympic medalists, could pass for an underfunded YMCA. The world's highest-performing schools – those in Finland and South Korea – feature austere classrooms that look as if they haven't changed since the 1950s.

The point of this tip is not moral; it's neural. Simple, humble spaces help focus attention on the deep-practice task at hand: reaching and repeating and struggling.

5. Figure out if it's a hard skill or a soft skill

Every skill falls into one of two categories: hard skills and soft skills. Hard, high-precision skills are actions that are performed as correctly and consistently as possible, every time. They tend to be found in specialised pursuits – such as a tennis player serving, or any precise, repeating athletic move; a child performing times tables; a worker on an assembly line, attaching a part. Here, your goal is to build a skill that functions like a Swiss watch – reliable, exact, and performed the same way every time, automatically, without fail.

Soft, high-flexibility skills, on the other hand, are those that have many paths to a good result, not just one. These skills aren't about doing the same thing perfectly every time, but rather about being agile and interactive; about instantly recognising patterns as they unfold and making smart, timely choices. Soft skills tend to be found in broader, less-specialised pursuits, especially those that involve communication, such as: a football player sensing a weakness in the defence and deciding to attack; a stock trader spotting a hidden opportunity; a novelist instinctively shaping the twists of a complicated plot. With these skills, we are not trying for Swiss-watch precision, but rather for the ability to quickly recognise af pattern or possibility, and to work past a complex set of obstacles.

The point of this tip is that hard skills and soft skills are different (literally, they use different structures of circuits in your brain), and thus are developed through different methods of deep practice.

6. Honour the hard skills

Most talents are not exclusively hard skills or soft skills (see above), but rather a combination of the two. For example, think of a violinist's precise finger placement to play a series of notes (a hard skill) and her ability to interpret the emotion of a song (a soft skill). The point of this tip is simple: prioritise the hard skills because in the long run they're more important to your talent.

At Spartak, the Moscow tennis club, there is a rule that young players must wait years before entering competitive tournaments. "Technique is everything," said a coach, Larisa Preobrazhenskaya. "If you begin playing without technique it is a big mistake."

You might be surprised to learn that many top performers place great importance on practising the same skills they practised as beginners. The cellist Yo-Yo Ma spends the first minutes of every practice playing single notes on his cello.

These performers don't say to themselves, "Hey, I'm one of the most talented people in the world – shouldn't I be doing something more challenging?". They work on the task of honing and maintaining their hard skills, because those form – quite literally – the foundation of everything else.

7. Don't fall for the prodigy myth

Most of us grow up being taught that talent is an inheritance, like brown hair or blue eyes. Therefore, we presume that the surest sign of talent is early, instant, effortless success, ie, being a prodigy. In fact, a well-established body of research shows that that assumption is false. Early success turns out to be a weak predictor of long-term success.

Many top performers are overlooked early on, then grow quietly into stars. This list includes Charles Darwin (considered slow and ordinary by teachers), Walt Disney (fired from an early job because he "lacked imagination"), Albert Einstein, Louis Pasteur, Paul Gauguin, Thomas Edison, Leo Tolstoy, Fred Astaire, Winston Churchill, Lucille Ball, and so on. One theory, put forth by Dr Carol Dweck of Stanford University, is that the praise and attention prodigies receive leads them to instinctively protect their 'magical' status by taking fewer risks, which eventually slows their learning.

The talent hotbeds are not built on identifying talent, but on constructing it. They are not overly impressed by precociousness and do not pretend to know who will succeed. While I was visiting the US Olympic Training Centre at Colorado Springs, I asked a roomful of 50 experienced coaches if they could accurately assess a top 15-year-old's chances of winning a medal in the Games two years from then? Only one coach raised his hand.

If you have early success, do your best to ignore the praise and keep pushing yourself to the edges of your ability, where improvement happens. If you don't have early success, don't quit. Instead, treat your early efforts as experiments, not as verdicts.

8. Five ways to pick a high-quality teacher or coach

Great teachers, coaches, and mentors, like any rare species, can be identified by a few characteristic traits. The following rules are designed to help you sort through the candidates and make the best choice for yourself.

1) Avoid someone who reminds you of a courteous waiter.

2) Seek someone who scares you a little. Encounters with great coaches/mentors tend to be filled with: feelings of respect, admiration, and, often, a shiver of fear. This is a good sign. Look for someone who:

– watches you closely: he is interested in figuring you out – what you want, where you're coming from, what motivates you.

– is action-oriented: she often won't want to spend a lot of time chatting – she'll want to jump into a few activities immediately, to get a feel for you and vice versa.

– is honest, sometimes unnervingly so: he will tell you the truth about your performance in clear language. This stings at first. But it's the information you can use to get better.

3) Seek someone who gives short, clear directions. Great teaching is not an eloquence contest; it is about creating a connection and delivering useful information.

4) Seek someone who loves teaching fundamentals. Great teachers will often spend entire practice sessions on one seemingly small element – for example, the way you grip a golf club, or the way you pluck a single note on a guitar.

5) Pick the older person. Teaching is like any talent: it takes time to grow. That's not to say there are no good teachers under 30, nor that every coach with grey hair is a genius. But all things being equal, go with someone older.

Copyright © Daniel Coyle 2012. Extracted from 'The Little Book of Talent' by Daniel Coyle, published by Random House Books on 6 September. To order a copy at the special price of £8.99 (usually £9.99), including p&p, call Independent Books Direct on 0843 0600 030

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies