Are there now so many patents in Silicon Valley that it's impossible to innovate?

Rhodri Marsden reports from the legal frontline

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 13 May, a Glasgow software developer, James Thomson, received a package via FedEx. After examining its contents, he fired up his Twitter account to convey some news: "Just got hit by very worrying threat of patent infringement lawsuit."

The letter referred to PCalc, Thomson's highly regarded specialist calculator for the iPhone. Following Apple guidelines, Thomson had included a screen within the app that offered users paid upgrades or extensions to the calculator – extra functionality for engineers or programmers or different colours. But a company based in Texas, called Lodsys, claimed they had invented this way of selling add-ons. With PCalc available through iTunes in the United States, Thomson had unwittingly put himself in the firing line.

This incident caused much disquiet at Apple and many observers questioned whether a vendor merely advertising and selling his own wares was really a patentable idea. But it is just one of thousands of current examples of alleged technological patent infringement in the US. Many believe the legal ramifications will suffocate innovation worldwide. American legislators, for their part, seem either unwilling or unable to address the situation.

Barely a day goes by without a big technology firm having to deal with a new complaint from a disgruntled patent owner. For example, as soon as the corks had finished popping over Spotify's recent launch in the US, a lawsuit was filed by a company called PacketVideo that claimed infringement of its patent of a "device for the distribution of music in digital form". Last month Apple had to pay out $8m (£5m) to a company called Personal Audio after the iPod was deemed to contain its patented "audio program player including a dynamic program selection controller".

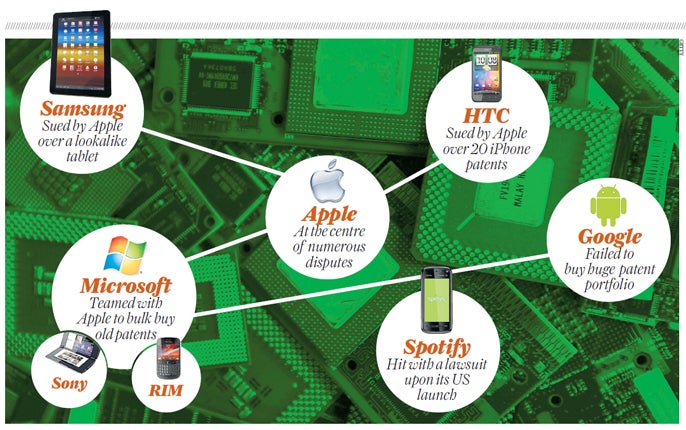

But it's not just about patent owners – some perfectly justified – grabbing themselves a chunk of the wealth generated by the technology industry. There's much industry infighting, too. Oracle is suing Google over features of the latter's mobile operating system, Android. Microsoft is also suing Motorola over Android-related issues. Yesterday Apple won a suit in a German court that accused Samsung of copying of the iPad's "look and feel" for its Galaxy tablet. Samsung is gearing up a response amid its much-hyped Galaxy 10.1 tablet being seized by EU customs officials as a result of the case.

Apple is also accusing HTC of infringing 20 of its iPhone-related patents; meanwhile, HTC is countersuing over five patents of theirs.

With the number of US patent lawsuits rising by 20 per cent in the first six months of this year over the same period last year, many people are questioning whether innovation is taking a back seat to litigation. In the world of music and art, copyright is usually a black-and-white issue; you've either copied someone else's work or you haven't. But patents provide a certain amount of scope around your idea and that grey area has become a prime target for legal disputes. "The Patent Office examiners determine the scope of an allowed patent," says Simon Davies, chairman of the computer technology committee of the Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys. "They don't always get it right."

The accusation levelled against the US Patent and Trademark Office is that they've issued too many patents with too broad a scope for too long. Notable patents from recent history include a "method of refreshing a bread product" (basically toast) and the crustless peanut butter-and-jam sandwich, both approved in 1999.

While these are frivolous examples, the patents covering nebulous business methods and computer-software techniques are causing arguments to flare up; hundreds, if not thousands, of such patents have overlapping remits, thanks partly to a collective rush to patent computer and internet-related ideas as the sector became more commercially significant.

A company called Segan LLC recently sued Zynga, the hugely successful firm behind online games such as Farmville, alleging infringement of one of its patents, namely: "a system and method for viewing content over the internet wherein a user accesses a service-provider server to view a character icon provided by the service provider to a user interface device." As Joe Osborne, from games.com, noted in a blog post: "Does Segan mean every online video game ever?"

Some people believe a situation has arisen where it's almost impossible to offer a new software service without infringing a number of patents and that the lawsuits targeted at independent software developers – such as Thomson – may start to generate a disincentive to create and innovate. James Bessen, a lecturer at Boston University, expressed his concern to The Huffington Post: "We have this terrible situation where there are thousands of patents filed each year where we don't know what they cover until somebody's been through a lawsuit."

And with a reported backlog of some 700,000 patent applications currently waiting to be processed in the US, there doesn't appear to be much hope of those patents being assessed with any greater stringency.

Impartial observers may conclude that this is creating a field day for lawyers and a nightmare for the technology industry, so software patents are thus inherently bad. Simon Davies offers two reasons why sympathies rarely lie with the infringed parties: "One is that you don't have to copy something to infringe a patent. You might independently come up with an idea and believe it's your creation, but even if you can prove that, you could still be infringing.

"The second is that, unlike music copyright, which is a moral right, patents are an economic right. People are prevented from independently creating things in order to protect profits. And you may not share that economic view."

Patents should protect the incomes and reputations of innovators, but the recent escalation in patent-related legal activity has seen fortunes being paid to companies that manufacture and invent nothing, and merely enforce patents. They're known – occasionally unfairly – as patent trolls.

The big technology corporations have been forced to fight back against the so-called trolls by using methods similar to those of the trolls themselves. Thousands of patents – particularly in the field of mobile communication – are being amassed by companies such as Microsoft and Apple; last month an auction of a portfolio of more than 6,000 such patents owned by the bankrupt firm Nortel Networks was sold to a consortium that included Apple, Microsoft, Sony and RIM (the company behind the BlackBerry) for $4.5bn.

Google, which failed in its bid to secure that same portfolio, has since criticised the escalating patent war. Some have criticised Google for being a poor loser of that hotly contested auction, but it's hard to interpret the defensive amassing of such a huge quantity of patents – not to be used for innovation but simply for legal action – as anything other than symptomatic of a broken system.

"The Nortel patents were valuable and had a lot of credibility," Davies says. "But the sense of owning a patent portfolio as a deterrent has become a significant commercial reality."

What effect do these arcane battles have on us, the consumer? It's perhaps inevitable that companies paying vastly over the odds for a stack of patents will pass on those costs to us via price hikes, but with the largest technology firms locked in a stalemate of mutually assured destruction, it's the effect on independent innovators such as Thomson that's of greatest concern. The problem is recognised at the highest levels of the US government – Barack Obama himself has called for reform – but there are many powerful vested interests in the patent system from both the banking and pharmaceutical sectors that have vastly conflicting priorities.

A single system doesn't seem to work in the internet age, but implementing multiple systems is fraught with complex legal issues and fearsome lobbying. Everyone would surely agree that ideas have value. But what constitutes an idea, and how much value it should have, will continue to provoke bitter arguments.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments